I wrote a static site generator (SSG) in pure bash to replace Jekyll, and allow myself to hand-write my site from scratch.

Now, why would I use an SSG in the first place when my goal is to hand-write

the site? Why would I torture enjoy myself by writing an SSG in pure

bash? Why not just use a fully-featured SSG or site template that a lot of

other people use?

Let's answer those questions, and discuss my thoughts on the resulting tool, as well as my initial experience using it to build this site.

Step One

Become disillusioned with the thing.

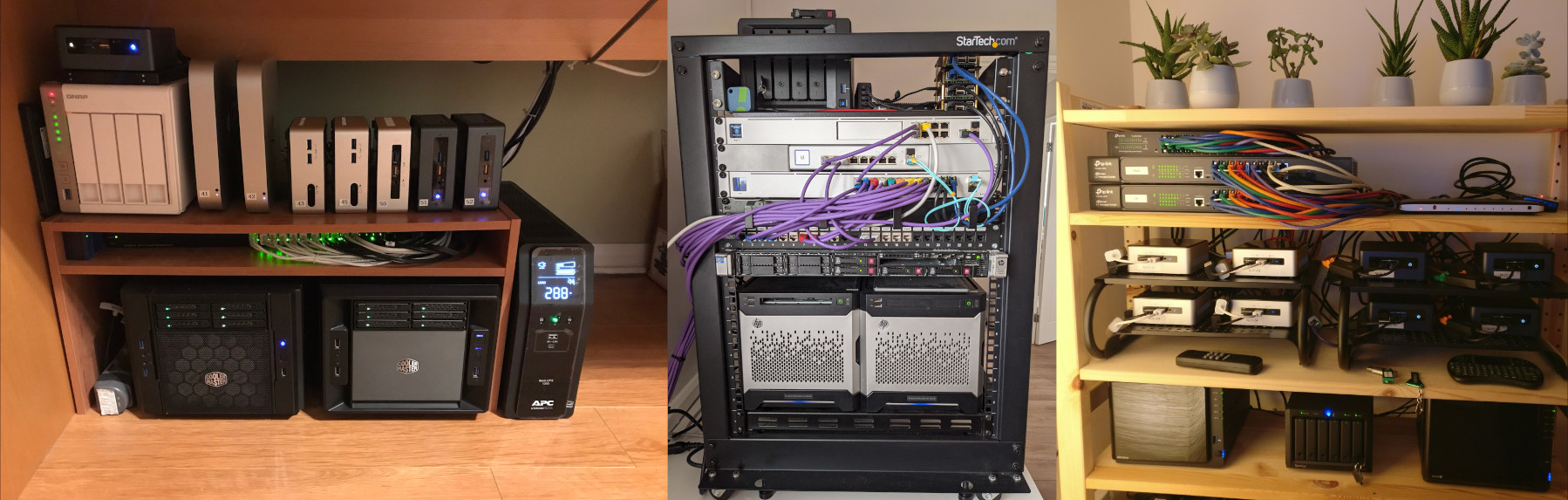

For years, I had used Jekyll to build my site. I liked the flexibility of using YAML, Markdown, and Liquid templating to turn directories of posts and other data/collections into nicely-formatted HTML pages. Things were peaceful in the garden that I had cultivated.

Eventually, I came to a point where I felt a friction in the process; my tools were chafing me, but why? I realized that my frustrations were not necessarily in what the tools were doing, but how they were doing it. Jekyll is a Ruby application; you must have Ruby installed on your machine in order to use it. I have never, not once, found myself interested in writing anything in Ruby. After auditing the packages installed on my systems, I found that Jekyll was the only app I used that required Ruby as a dependency. I also began to wonder what these tools were driving me to do, and whether I felt comfortable with the idea of my tools influencing the direction and content of my site more than my brain. Reading through the documentation for Jekyll and the Liquid templating language left me with an insatiable lust for utilizing as many features of the two that I could. This is a bad idea. This is how software becomes bloated. This is how we create things which cannot sustain themselves.

I could feel the power of the SSG was drawing me closer and closer to this place I did not want to be in.

It was time for Jekyll to go.

Step Two

Deny yourself the thing.

So I removed Jekyll (and consequently Ruby) from my system. Would I move to a different, less powerful SSG, then? Hell no!

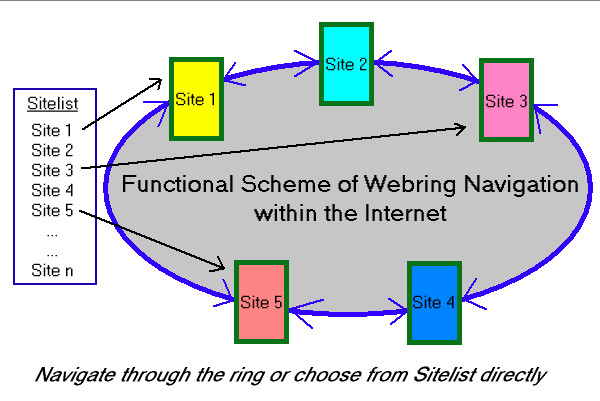

I began to read up on the small web, the minimalist web, the handmade web. I became increasingly enamored with the idea of re-writing my site from scratch, without the use of any templating or external programs.

In particular, I was inspired by this site and the way it uses CSS to emulate the behavior of a single-page application . In fact, the bones of this site stick pretty closely to that formula, and the entire thing remains a single HTML file. Of course, there is a separate CSS stylesheet, and plenty of static image files, PDFs, etc.

So I said, "Fuck it! I'll do it myself!" And that's exactly what I did.

And that's when I started chafing again.

Step Three

Accept that you could use the thing.

While it was certainly possible to write everything by hand, that also meant I had to:

- Update everything myself. This includes the copyright year and date of last update in the aside footer, among other things.

- Maintain unique <section> tag ids myself. This is because each "page" of the site needs to be contained in an HTML <section> tag with a unique id attribute. These ids also need to be maintained across links within the site that point to those pages.

- Maneuver around an increasingly large HTML file in my editor.

- ...and much more.

Perhaps I don't need to explicitly mention this, but these tasks were tedious, annoying, and getting in the way of my enjoyment of cultivating this website.

Something needed to be done about this, or else I would never touch this thing ever again, and that would be sad. So I did what I always do in these sorts of situations; I went about writing my own bespoke solution to problems that other people much smarter and more talented than I have already solved.

Step Four

Identify what you want the thing to do.

Because I still had that bad taste in my mouth of unnecessary dependencies, I decided to write my solution in pure bash. No matter what system I need to build my site on, I can be damn sure that it'll have bash installed on it.

Other things I needed this tool to do included:

- Automatically update the aforementioned dates in the footer.

- Organize my blog posts into reverse-chronological order.

- Generate an RSS feed of those blog posts.

- Ensure (as much as is reasonable) that page ids are unique.

- Identify external links and open them in a new tab.

- Allow images to load lazily.

- Generate lightboxes for some images (without any JavaScript). Doing things without JS is important to me for this site. These inline footnotes you're reading are also implemented using CSS only, no JS required.

- Take a directory of files and collapse it into one HTML file.

- Take static files and move them into a final site directory.

- Allow for draft files that are not included in release builds.

- Be simple enough that I don't tear my hair out when modifying it.

This may seem like a daunting task, but keep in mind that a major thing this tool would not need to do is parse some external templating language or reference a library of "collections" and "filters" and such. In fact, the resulting script comes in at almost exactly 300 source lines of code (SLOC) at time of writing. Turns out, removing complex features intended for increasingly generic use cases and replacing them with custom solutions meant for specific use cases leads to a much smaller tool.

Now all I had to do was actually write the damn thing. Let's see how I did it.

Step Five

Make a thing that does what you want.

Many of the strange "bash-isms" you are about to see in my code were lifted from, or otherwise inspired by, the brilliant Pure Bash Bible .

The script handles updating certain dates by looking for a particular string in the HTML code and replacing that string with a date generated and formatted using a neat little 'printf' trick .

Show/Hide Code Block

interpolate() {

local pattern=$1

local replacement=$2

local num_replace=${3:-all}

local temp

temp="$(<"$BUILD")"

case $num_replace in

once)

temp="${temp/$pattern/$replacement}" ;;

all)

temp="${temp//$pattern/$replacement}" ;;

esac

echo "$temp" > "$BUILD"

}

format_date() {

local -n ptr=${1}

local fmt=$2

printf -v ptr "%($fmt)T\\n" "-1"

}

...

interpolate_dates() {

local copyright_year && format_date copyright_year '%Y'

interpolate '%COPYRIGHT_YEAR%' "$copyright_year"

local modification_date && format_date modification_date '%B %d, %Y'

interpolate '%MODIFICATION_DATE%' "$modification_date"

}

The '$BUILD' variable in the above code block is used to track the current HTML file generated by the script. I often read it into a string, modify that string in some way, then write it back to the file.

NOTE

In many of these blocks you will see me interpolate strings of the form "%PATTERN%". In my actual script, I use '{' and '}' to enclose these patterns, but if I include that syntax in these code blocks, my script will try to interpolate them as well, which I don't want. So I use '%' to "fool" my script into leaving them alone.

The script accomplishes writing blog posts and rolling them into an index page by iterating over a '_posts/' directory and doing some more interpolations. We also programmatically determine the publish date, post title, and link id based on the filename of the post.

Show/Hide Code Block

output() {

local string=$1

local dest=${2:-$BUILD}

echo "$string" >> "$dest"

}

...

parse_post_date() {

local -n ptr=${1}

ptr="${ptr%% *}"

ptr="${ptr//-/\/}"

}

parse_post_title() {

local -n ptr=${1}

ptr="${post#* }"

ptr="${post_title%.*}"

}

parse_post_href() {

local -n ptr=${1}

local post_date post_title

post_date="$ptr" && parse_post_date post_date

post_title="$ptr" && parse_post_title post_title

ptr="blog/$post_date/$post_title"

}

escape_ampersands() {

local -n ptr=${1}

ptr="${ptr//\&/\\&}"

}

write_posts() {

# Iterate over posts in reverse

# This puts most recent posts at the top

local posts=("$POSTS_DIR"/*.html)

local post post_date post_title post_href post_content post_string

local post_list=''

local i

for ((i=${#posts[@]}-1; i >= 0; --i)); {

post="${posts[$i]##*/}"

[[ "$post" == *DRAFT* && $DRAFT_MODE == 0 ]] && continue

post_content="$(<"${posts[$i]}")" && escape_ampersands post_content

post_date="$post" && parse_post_date post_date

post_title="$post" && parse_post_title post_title

post_href="$post" && parse_post_href post_href

# Output the actual post page

output "<section id=\"$post_href\" class=\"blog\">"

post_string="$(<"$PARTS_DIR/post.html")"

post_string="${post_string//\{POST_TITLE\}/$post_title}"

post_string="${post_string//\{POST_DATE\}/$post_date}"

post_string="${post_string//\{POST_CONTENT\}/$post_content}"

output "$post_string"

output '</section>'

# Add the post to the post list

post_list+='<div>'

post_list+="<a href=\"#$post_href\">"

post_list+="<h3>$post_title</h3>"

post_list+='</a>'

post_list+="<small>Posted on $post_date</small>"

post_list+='</div>'

}

interpolate '%BLOG_POST_LIST%' "$post_list"

}

One of my requirements was the inclusion of a "Draft Mode", which you can see me use in the above block. I look for the user to pass in a '-d' command line argument to see if we should build the site in Draft Mode or not. If the script is not in Draft Mode, then any file with the string 'DRAFT' anywhere in its filename will be skipped over. This is not a perfect solution, as I often find myself modifying some part of the CSS for a DRAFT file, but I also have some production change I want to make. I don't want to rename the CSS file to have 'DRAFT' in its name, so I compromise by manually selecting hunks of the file to commit with 'git add -p'.

You may have also noticed the '$PARTS_DIR' variable in the above code block. I use this directory to store little pieces and parts of HTML that get included elsewhere, like the header, footer, and post layout. In this way, it kind of fulfills the role of both an '_includes/' and '_layouts/' directory.

We can use similar logic to writing posts in order to generate an RSS file by iterating over the blog posts once again.

Show/Hide Code Block

write_rss_feed() {

local posts=("$POSTS_DIR"/*.html)

local post post_title post_href post_date

output '<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8" ?>' "$RSS"

output '<rss version="2.0">' "$RSS"

output '<channel>' "$RSS"

output "<title>$SITE_TITLE</title>" "$RSS"

output "<link>$SITE_BASE_URL</link>" "$RSS"

output "<description>$SITE_DESCRIPTION</description>" "$RSS"

# Iterate over posts in reverse

# This puts most recent posts at the top

local i

for ((i=${#posts[@]}-1; i >= 0; --i)); {

post="${posts[$i]##*/}"

[[ "$post" == *DRAFT* && $DRAFT_MODE == 0 ]] && continue

post_date="$post" && parse_post_date post_date

post_title="$post" && parse_post_title post_title

post_href="$post" && parse_post_href post_href

output '<item>' "$RSS"

output "<title>$post_title</title>" "$RSS"

output "<link>$SITE_BASE_URL/#$post_href</link>" "$RSS"

output "<description>$post_date - Blog Post</description>" "$RSS"

output '</item>' "$RSS"

}

output '</channel>' "$RSS"

output '</rss>' "$RSS"

}

We've seen in some of the above code snippets that we are generating the enclosing <section> tags for some pages. The id is programmatically generated, which effectively fulfills my requirement of maintaining unique ids across pages, to a certain extent.

For opening external links in a new tab, we take advantage of some <a> tag attributes, interpolating them into every marked link in our site. Now, remembering to mark external links with this placeholder string is a huge pain, and goes directly against what this tool is supposed to prevent. So, I also add a check for any unmarked external links using a regex match. If one such link is found, the script will print it to the terminal so the user can see which links they need to go in and add the marker to. Again, it's not a perfect solution, but directly interpolating without using a marker was giving me a lot of trouble with infinite loops, or not finding all external links properly. I settled for a "good enough" solution instead.

Show/Hide Code Block

modify_external_links() {

check_for_unmarked_external_links

interpolate '%EXT_LINK%' 'target="_blank" rel="noopener noreferrer"'

}

check_for_unmarked_external_links() {

local line

while read -r line; do

[[ $line =~ \<a\ *href=(\".*//.*\")\ *\> ]] && {

echo "External link ${BASH_REMATCH[1]} has no %EXT_LINK% mark"

}

done < "$BUILD"

}

Perhaps in the future I will modify this behavior so that instead of reporting missing marks, we actually just interpolate the external links directly, eliminating the marks entirely.

Making images load lazily is much easier than a lot of the other logic, just using a simple interpolation.

Show/Hide Code Block

make_images_lazy() {

interpolate '<img ' '<img loading="lazy" '

}

For generating lightboxes, we iterate over all the files within our 'artwork/' directory, and for each image file, we write out a link to another "page" that functions as a lightbox. It also functions as a link back to the original page that the image was hosted on.

Show/Hide Code Block

write_image_lightboxes() {

local image extension image_id origin

for image in "$STATIC_DIR"/artwork/**/*; {

[[ "$image" == *DRAFT* && $DRAFT_MODE == 0 ]] && continue

extension="${image##*.}"

case $extension in

jpg|png)

image_id="${image#*/}" ;

origin="${image_id%/*}" ;

[[ $origin != *.* ]] && {

write_lightbox "${image:1}" "$image_id" "$origin"

} ;;

*)

;;

esac

}

}

write_lightbox() {

local image_src=$1

local image_id=$2

local origin=$3

output "<a id=\"$image_id\" class=\"lightbox\" href=\"#$origin\">"

output "<img src=\"$image_src\" />"

output '</a>'

}

As for the other requirements, they've basically been fulfilled by the nature of what our script has become, or can be solved with very simple calls to 'mv' and 'cp'.

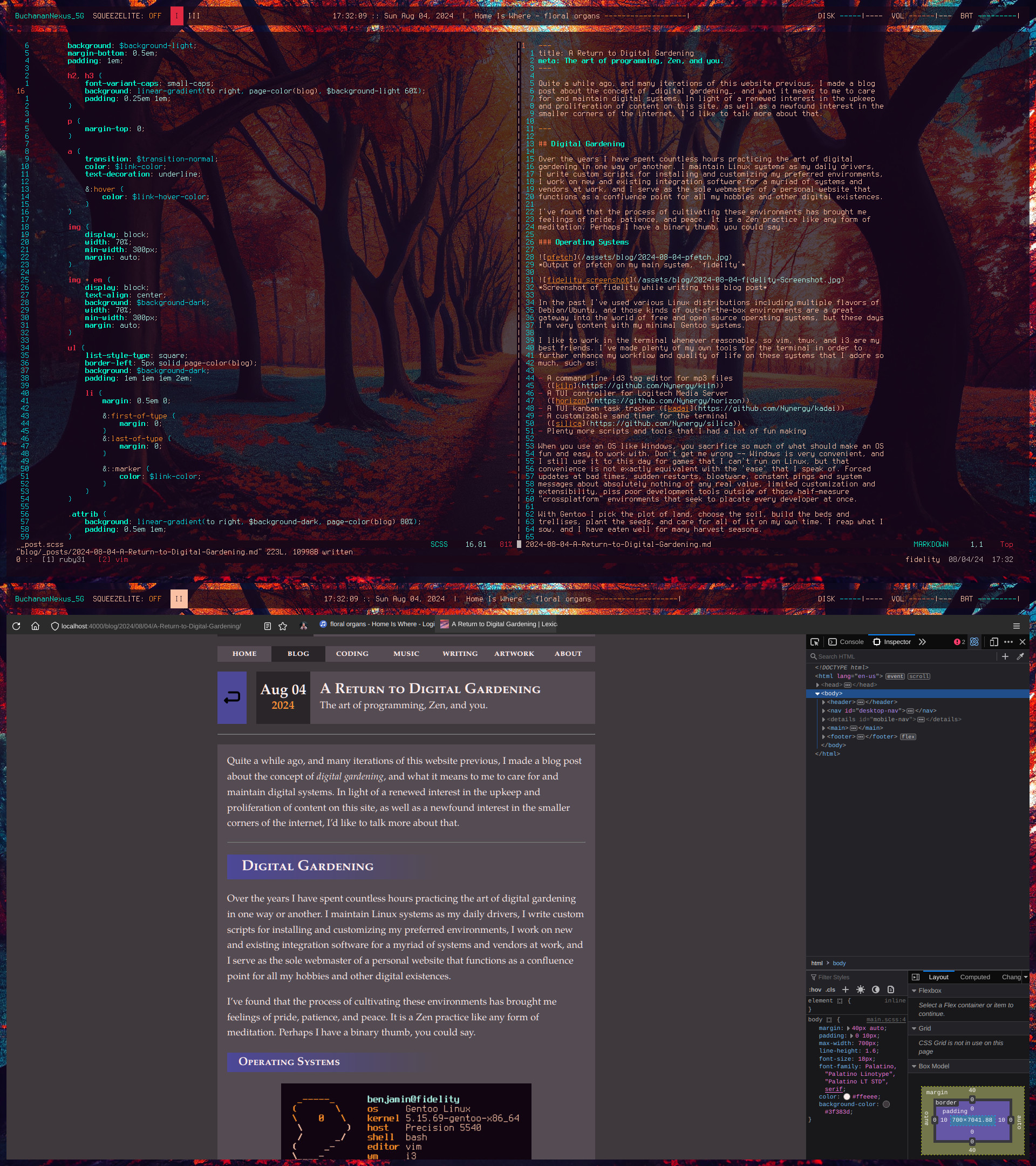

The only other pain point I had when trying to emulate the behavior of a single-page application was that the CSS I grabbed from my inspiration site was meant to be used with absolute positions and overlays and such. I don't like to use that kind of style, so I needed to modify my CSS to replicate the behavior in a different way.

I ended up with the following code to control which "page" is shown.

Show/Hide Code Block

section,

section:target ~ #home,

#home:has(~ section:target) {

display: none;

}

#home, section:target {

display: block;

}

Originally this code was a bit different, but I had to change it to allow the

home page to exist in any position relative to other pages. Before, the CSS I

used required the home page to always be the first page, but I didn't want to

bake that requirement into the logic of my script. So, I landed on this

admittedly dense CSS declaration.

For those not well-versed in CSS declarations and selectors, what the above

two declarations say is:

1. All sections are display: none.

2. All elements with id 'home' (#home) that exist adjacent to a targeted

section are display: none (including 'left-of' and 'right-of').

3. All other targeted sections and #home elements are display: block.

This results in the behavior that any targeted section is the displayed

page, and if nothing is targeted, then the home page is displayed.

With all that out of the way, I could now properly include generic multi-level pages in my generated HTML file by iterating over a '_pages/' directory. Using a glob allows nested pages, such as the ones I use for the Music section of this site.

Show/Hide Code Block

output_content() {

local filepath=$1

local dirname="${filepath%%/*}"

local page_id="${filepath#*/}"

page_id="${page_id%.*}"

local page_class="${page_id%%/*}"

[ -f "$filepath" ] && {

[ "$dirname" == "$PAGES_DIR" ] && \

output "<section id=\"$page_id\" class=\"$page_class\">"

output "$(<"$filepath")"

[ "$dirname" == "$PAGES_DIR" ] && \

output '</section>'

}

}

...

write_pages() {

local page

for page in "$PAGES_DIR"/**/*.html; {

[[ "$page" == *DRAFT* && $DRAFT_MODE == 0 ]] && continue

output_content "$page"

}

}

Step Six

Use the thing. Rejoice.

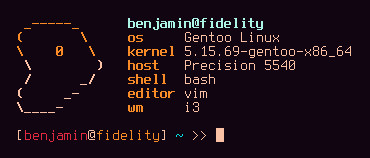

And so, totem The name comes from the way it structures the resulting HTML file. It "stacks" the various sections on top of one another, resulting in a long file that you could say resembles a totem pole . was born, and Lexica Chromatica reborn alongside it.

As with all things, both the site and the tool used to build it are not final. There will be changes, fixes, workarounds, alterations, compromises, etc. But I am very pleased with the results thus far.

totem allows me to continue writing the HTML of my site by hand, while also eliminating much of the friction I experienced with the more tedious tasks of website maintenance. I already feel more at home in this iteration of the site, and I don't feel the draw of extra features leading me to fill the site with useless pages it doesn't need.

I built a tool that does just enough for me, and nothing more. It's portable, not reliant on external dependencies, small, and simple. Most programmers today could learn a thing or two about that sort of brevity.

If you want to read more about how totem works, and even build an example site with it, you can follow the link at the top of this section and clone the repo for it. However, I would not suggest using it as your own SSG unless you feel comfortable making changes to it, or otherwise using a similar site structure to mine. While I did bake some generic functionality into the script, I did not intend for it to be used in any serious context outside of my own website. Your mileage may vary.

If you're at all of a technical mind, or perhaps already proficient in writing programs, I'd encourage you to give rolling your own SSG a shot. Or maybe take the time to create another tiny tool that solves another of your problems. It's rewarding, and using software that you actually understand inside and out is an important part of digital independence, especially in today's hyper-capitalist techno-feudalist reality.

Craft your own tools. Break the chains they put you in.

Step Seven

Ponder the thing. Perhaps write a blog post.